Spending Watch: The Unpleasant Arithmetic of a California Wealth Tax

Wayne Winegarden

October 2025

A just proposed initiative to impose a one-time wealth tax on billionaires summarizes why California has fallen from the fourth to the fifth largest economy in the world. State policymakers continually view the private sector as a piggybank to be raided whenever it pleases them. The irony is that the state’s anti-growth policies are making the state’s long-term budget outlook worse, while also undermining our prosperity.

The logic of the wealth tax is as simplistic as it is wrong. According to the authors, 200 billionaires live in California with a total net worth of $2 trillion. They then deceptively claim that billionaires are undertaxed relative to other Californians by comparing their current annual state income taxes paid to their wealth. California does not impose taxes on wealth (at least yet). It taxes income. Therefore, this comparison is completely irrelevant. But it is enlightening.

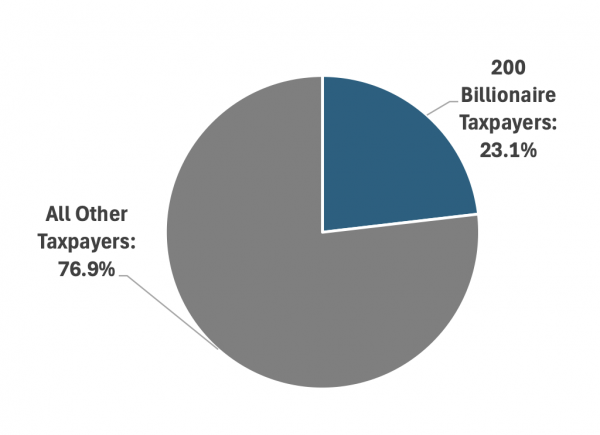

Taking the authors’ numbers to be accurate, then the 200 billionaires paid $30 billion in taxes – paying 1.5 percent on $2 trillion in wealth. Presuming these are mostly income taxes, and given that total income tax revenues for FY2025-26 are expected to be $129.6 billion, these 200 billionaires are paying for over 23 percent of the state’s total income tax revenues. As the FY2025-26 e-budget noted, the top one percent of income earners, around 170,000 taxpayers, account for more than 40 percent of the total personal income tax collections. This overdependence on a minority of taxpayers is due to California’s highly progressive tax system.

The 200 Billionaires Targeted by the Wealth Tax Cover More Than 23 Percent of the State’s Personal Income Tax Revenues

The authors also admit that billionaires have a “unique ability to control the timing, location, and amount of income tax that they pay.” The politics of envy aside, this is precisely the problem for the state. The initiative’s own numbers – $2 trillion in assets owned by 200 billionaires – indicate that the average billionaire (worth $10 billion) will have to pay the state $500 million.

This is an unrealistic tax bill because even billionaires don’t have $500 million laying around the house. Paying this tax bill would require these people to quickly liquidate their holdings, likely at a loss. This would create a huge incentive for these families to “change their location” and move out of the state. Should all these billionaires move to other states, then California would lose $30 billion in annual personal income tax revenues.

The proposal would also limit the annual expenditures from the one-time wealth tax to $25 billion each fiscal year. In other words, the state is risking a recurring $30 billion loss in personal income tax revenue for the hope of getting a $25 billion revenue boost.

Making this trade-off even worse, the one-time tax is supposedly a one-off wealth expropriation. Levying a 5 percent tax on $2 trillion in wealth – ignoring the unlikelihood that these revenues would ever be raised – would allow the state to deposit $100 billion into the Reserve Account. Even allowing for interest on these revenues, the tax would provide a short-term revenue boost – five years at best, assuming the full $25 billion is spent annually.

Put differently, the state is risking the loss of a larger long-term revenue source for a smaller temporary revenue boost. A clearly bad trade-off. Worsening this trade-off, just the chance that this wealth tax will be implemented could incentivize some billionaires to leave the state “just in case.” Not only will state tax revenues suffer as a result, but California’s economic vibrancy will take another hit.

California’s anti-growth policies, which include the exceptionally high tax burden, are taking a toll on the state’s long-run economic prospects. Without a course correction, falling to the fifth largest economy in the world won’t be the last economic downgrade that the Golden State will have to endure.

Wayne Winegarden, Ph.D. is a Sr. Fellow in Business and Economics and Director of the Center for Medical Economics and Innovation at the Pacific Research Institute