Reality-television stars are rarely consulted on matters of public policy. But in April, Realtor.com asked Tarek El Moussa to comment on the White House’s “Liberation Day” tariffs..

The Southern California entrepreneur, who rose to fame on the popularity of HGTV’s Flip or Flop franchise, warned that higher import taxes would harm “new-home builders” and “first-time buyers” the most — after all, “luxury buyers” could absorb greater costs. Aspiring homeowners, he averred, are “usually strapped for cash,” and “doing everything they can just to buy a house.”

Now that the second Trump administration has passed its one-year anniversary, all evidence indicates that El Moussa understands his industry well. America’s affordable-housing shortage predates The Donald’s return to the White House, but there is little doubt that his trade war erects a sizable obstacle before those looking to find a place of their own.

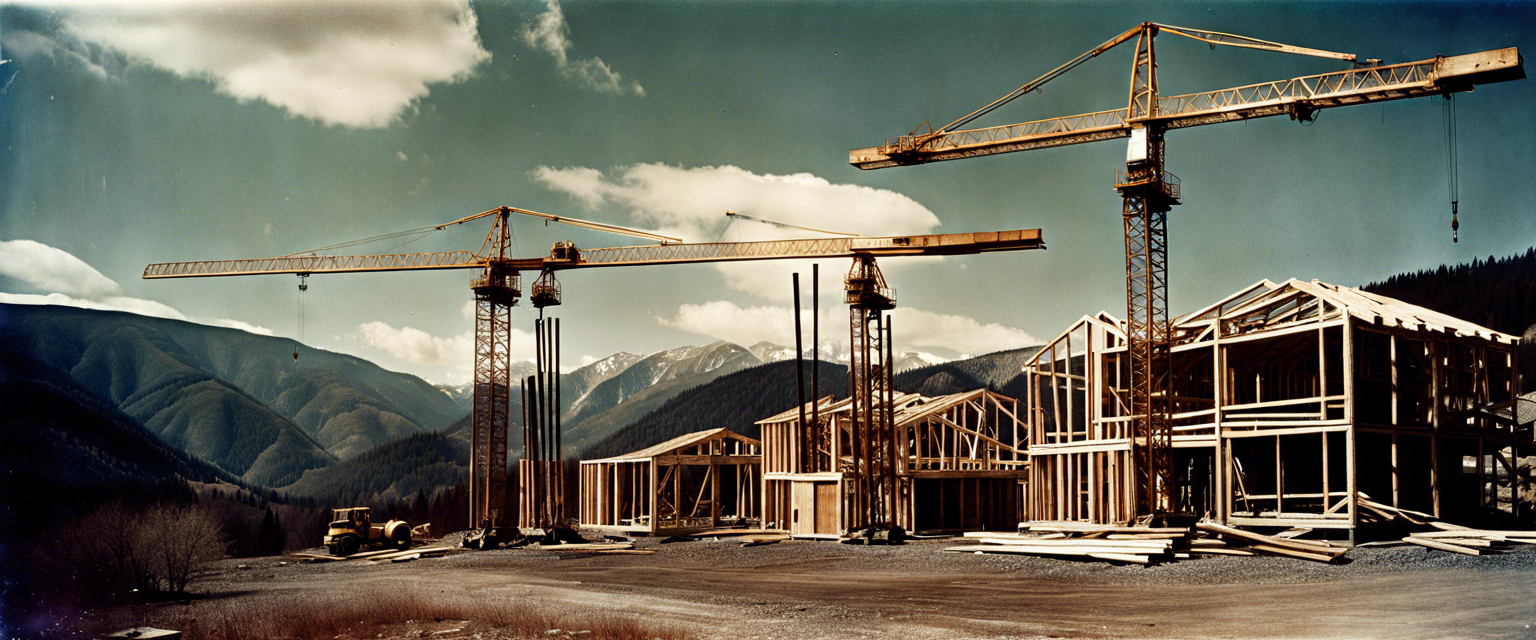

The construction industry is highly globalized. Per risk-management firm Verisk, the American floor-covering market’s “import reliance” is at 53%, and 25% of asphalt shingles (the dominant choice for home roofing) are sourced from abroad. HousingWire reported that in 2023, “the U.S. imported $215 million worth of gypsum,” the main ingredient of drywall, “with the majority coming from Spain, Mexico, and Canada.”

But materials not commonly thought of as housing inputs shouldn’t be overlooked. In February 2025, Trump “signed proclamations to close existing loopholes and exemptions to restore a true 25% tariff on steel and elevate the tariff to 25% on aluminum.” Several months later, in a decision former senator Phil Gramm and economist Donald J. Boudreaux slammed as “the most reckless trade action of the Trump presidency,” the levy for both rose to 50%.

Imports of steel and aluminum contribute significantly to home construction. The former is used for rebar, framing, roofing, cladding and fencing. Colorado-based Richardson Metals characterizes the latter as a “strong, lightweight material” with a wide range of applications, including “beams, frames and support systems,” “[a]rchitectural features,” “window frames, doors, trims and decorative facades,” and “[e]xterior finishes.”

Construction, according to the Copper Development Association, “accounts for nearly half” of Element 29’s U.S. consumption. The typical “single-family home uses 439 pounds” of the stuff. In July, Trump imposed a 50% t tariff on “all imports of semi-finished copper products and intensive copper derivative products.”

The National Association of Home Builders (NAHB) describes softwood lumber as “a key component in home building.” America’s neighbor to the north accounts “for roughly 85% of all U.S. … imports and … almost one-quarter of the supply in the U.S.” In September, POTUS hiked the preexisting tariff placed on the material. The following month, the premier of British Columbia growled that “Canadian wood has a higher tariff rate going to the United States than Russia does.”

While we’re on the subject of dead trees, it’s worth noting that the White House’s trade war extends beyond construction materials — to the objects that make a house a home. Last fall, “upholstered wooden products” were slapped with a 25% tariff, which rose to 30% on January 1st. In the same presidential proclamation, “kitchen cabinets and vanities” got hit by a 25% levy that doubled at the start of the New Year. Months earlier, the scope of steel tariffs was expanded to cover “cooking stoves, ranges, and ovens,” “combined refrigerator-freezers” and other major appliances.

Protectionists’ magical thinking holds that while their policies admittedly induce short-term pain, the inevitable result is long-term prosperity. For example, the president believes that tariffs “will bring the Furniture Business back to North Carolina, South Carolina, Michigan and states all across the Union.”

Yet if the history of trade conflicts teaches anything, it’s that promises of reshoring are often hollow. The Cato Institute notes that “both steel production and capacity utilization are below the level they were” when the first Trump administration imposed them in 2018.

Furniture for America, “a coalition of American companies — both domestic manufacturers and importers,” argues that protectionism will be no friend to its industry, either: “Tariffs cannot reopen factories that no longer exist, bring back thousands of workers who retired or moved on … nor reverse the interests and inclinations of today’s younger workers, who are attracted to higher-paying trades.” Lumber itself provides another red flag. America’s forests are vast, but not all trees are created equal. The University of Tennessee’s Andrew Muhammad and Adam Taylor explained:

The types of wood available in the United States are not always the same as what’s available from Canadian imports. For framing, contractors may prefer spruce, northern pines and fir, naturally abundant in Canada, because they are lighter and less likely to warp than southern yellow pine, which is abundant in the southern United States.

Copper faces a dubious domestic revival. In an analysis for the Center for Strategic and International Studies, Gracelin Baskaran and Meredith Schwartz outlined their reasons for skepticism. Given “substantial capital investment and long lead times” — in addition to “higher labor costs” — “the economics of developing new smelters do not add up right now.”

The Center for American Progress recently calculated that Trump’s tariff barrage “adds $17,500 in costs per new home.” Since “[h]igher construction costs slow the pace of new housing construction and prevent marginally profitable housing units from being constructed,” approximately “450,000 fewer new homes” will be “built over the next five years, through 2030, including more than 100,000 yearly from 2030 onward.”

Unfortunately, developers and aspiring homeowners shouldn’t look to the U.S. Supreme Court for much relief. Yes, a decision in the consolidated case seeking to overturn the “Liberation Day” levies is expected soon, and there is reason for free-traders to be optimistic. But at issue is presidential authority under the International Emergency Economic Powers Act. Many of Trump’s tariffs impacting housing — e.g., steel, aluminum, and copper — stem from actions taken under the Trade Expansion Act, a separate law that has survived multiple challenges before the high court.

“Make housing unaffordable forever”? It’s not likely to play well with voters in November.

D. Dowd Muska is a researcher and writer who studies public policy from the limited-government perspective. A veteran of several think tanks, he writes a column and publishes other content at No Dowd About It.