Demanding that drug prices in the U.S. equal overseas prices is akin to demanding that the price of all expensive handbags should equal the prices for the knockoffs that people purchase from street vendors.

Of course knockoff bags are cheaper. They violate the intellectual property rights of the bag’s maker, use inferior materials, and fail to abide by local taxes and regulations. Due to these realities, imposing a handbag price control policy set at the knockoff price would undermine the viability of the entire high-end handbag market.

The same thing is happening with innovative medicines. Countries like the U.K., Canada, and France impose price controls on these drugs that do not cover the $2.9 billion in capital costs required to develop innovative medicines. So of course they are cheaper. However, just like with handbags, demanding that the U.S. also impose uneconomical prices would collapse the innovative drug market.

Simply because it is inappropriate to set U.S. drug prices at the international rates does not mean that the problem of uneconomical international prices should be ignored. The U.S. should address this issue through international trade negotiations.

Just as the U.S. supports the intellectual property rights of numerous technology companies, our trade negotiators should ensure that other countries do not undermine the intellectual property rights of mostly U.S. biopharmaceutical companies. In other words, these countries need to significantly ease their price controls on innovative drugs.

While higher prices overseas would help alleviate some of the pricing pressures in the U.S., the fact remains that the U.S. drug pricing system is in dire need of reform. Two essential reforms include changes to the PBM market and the 340B drug discount program.

Starting with the PBM market, PBMs are intermediaries that manage the prescription drug benefits for insurers and government payers. However, PBM operations are opaque, their revenues streams complex and perhaps most importantly, their operations obscure the actual market price for medicines. Due to these flaws, prices for innovative medicines in the U.S. are inflated.

An analysis by Nephron Research shows that the rebates and fees that biopharmaceutical manufacturers paid to “PBMs and PBM contracting entities” made up 42% of total US brand sales in the commercial market in 2022.

In other words, $0.42 of every $1 spent on brand medicines for commercially insured patients in the US goes straight to PBMs.

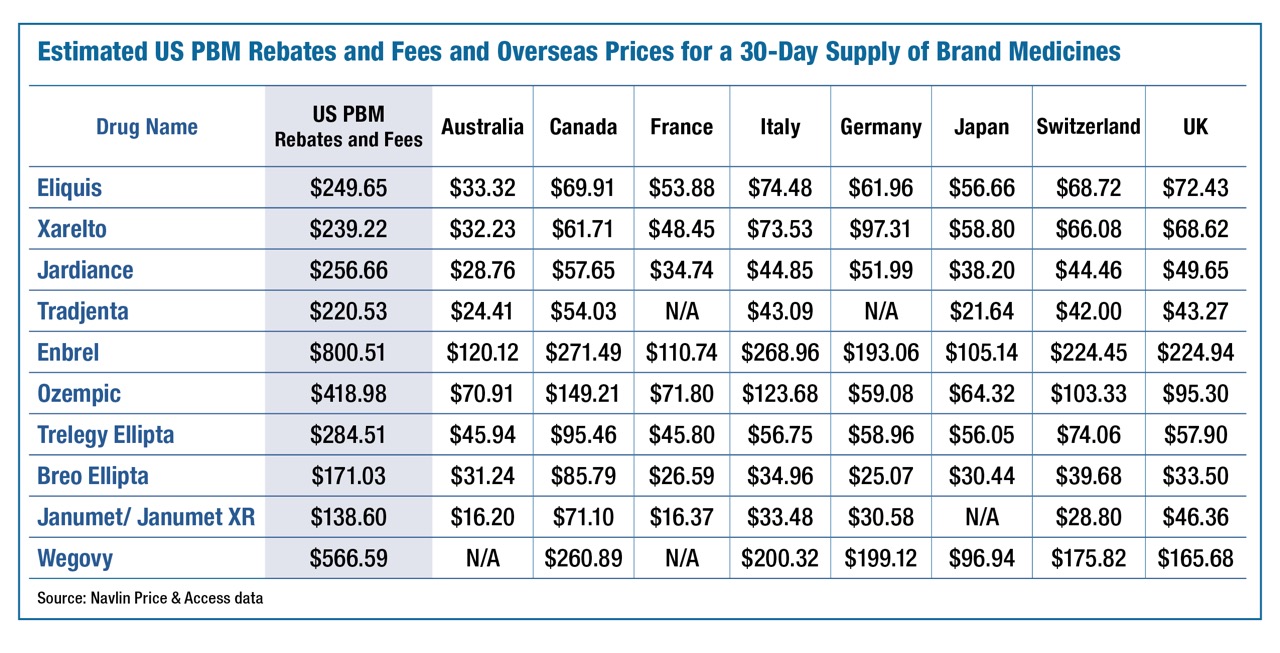

To put this in perspective, compare the 42 percent PBMs take to the price-controlled prices in other industrialized countries for specific medicines, see the table below. The calculations illustrate that just the costs of the industry middlemen in the U.S. exceed the prices in other OECD countries.

This cost difference demonstrates two problems: (1) the prices in other OECD countries are set at economically unviable levels; and (2) the costs of the industry middlemen in the U.S. is excessive. The proper venue for addressing the uneconomical pricing in other countries is through U.S. trade negotiations. The goal should be to encourage these countries to better respect the intellectual property rights of mostly U.S. based biopharmaceutical companies and set pricing in these countries that more closely reflect the actual costs of capital.

With respect to PBMs, as I argued in a recent Forbes commentary, the goal should be to implement “reforms, such as S.526, which focus on reining in PBMs’ inflationary impact and demanding greater price transparency.”

Another essential reform would address the adverse cost impacts caused by the 340B program. The 340B program was created to subsidize hospitals and clinics serving low-income populations to help them provide more care for these vulnerable populations at lower cost. To achieve this goal, 340B allows qualified hospitals to buy steeply discounted drugs and then resell them to Medicare or privately insured patients at full price and pocket the difference.

And that difference is large. In fact, the markups 340B hospitals charge on cancer medicines, for instance, exceed the prices of those medicines in eight OECD countries, often by 200% to 700%. For example, 340B hospitals markup up the cost of Keytruda by more than $20,000. This markup – all of which the hospital keeps as profit – is more than twice the price of the medicine in Canada, Italy, and the UK, more than four time the price in Australia, France, Germany, and Switzerland, and more than eight times the price in Japan.

Yet, as I document in JAMA Network, abuse of this well intentioned program has turned it into a profit center for large health systems that do not pass the savings on to patients and tend to provide less charity care than the average hospital. Due to the extreme profitability of the program, the program has experienced rapid growth. In 2009, the discounted value of 340B purchases was $4 billion. By 2023, these purchases had grown to $66 billion – a sixteen fold increase!

Due to the extreme growth of the program, its costs are now being shifted to other commercial and Medicare patients. Reining in 340B will help alleviate the rising prices on the broader market while still enabling the program to fulfill its intended purpose of helping vulnerable patients receive the care and medicines they need.

As the potential benefits from reforming PBMs and 340B exemplify, there are many opportunities to improve the efficiency of the U.S. pharmaceutical pricing system. Doing so can help improve affordability for patients while still maintaining the incentive to help patients living with untreated diseases.

It is essential that drug pricing reforms maintain this combination of improving affordability today while maintaining the incentive to innovate for tomorrow. The President’s MFN policy fails this test, which is why it should be jettisoned.

Dr. Wayne Winegarden is the director of the Center for Medical Economics and Innovation at the Pacific Research Institute, and is a PRI senior fellow in business and economics.