What will California cities do if the bullet train is derailed?

By John Seiler | May 16, 2025

California cities face numerous needs for mass transit at the local level. But lurking over any plans is the California High-Speed Rail project, which has soaked up funds since voters approved it 17 years ago with Proposition 1A.

A March 27 review by the Legislative Analyst’s Office found “a funding gap of roughly $7 billion for completing the Merced-to-Bakersfield segment.” And, “other factors could drive growth in the project’s funding gap,” including attacks by the new Trump administration, inflation and uncertainty over funds from the Greenhouse Gas Reduction Fund.

The next day Gov. Gavin Newsom defended it again on Bill Maher’s “Real Time.” Avoiding a direct answer on the whole project, Newsom said, “We at our own peril, we talk down to the people in the Central Valley.”

What if the project is canceled? How will that affect cities, not just those in the Central Valley, where construction is occurring, but for the projected tracks all the way down to San Diego?

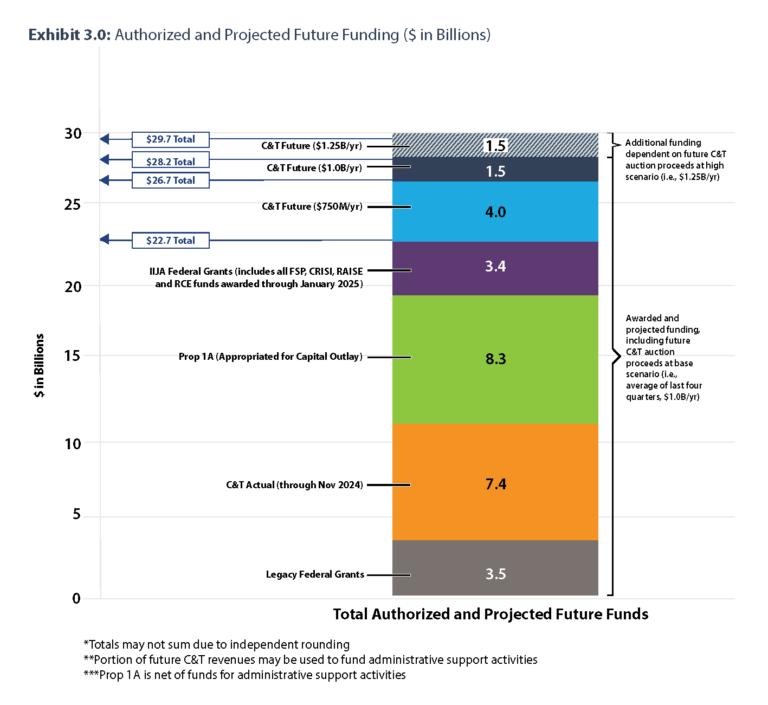

First, consider the funding chart from the California High-Speed Rail Authority’s March 2025 biennial Project Update Report. It notes, “Under these assumptions, total remaining funding through 2030 is $14.9 billion, after taking into account expenditures through December 31, 2024.” Here’s the chart.

A key figure is at the top right, on Cap and Trade: “Additional funding dependent on future C&T auction proceeds at high scenario (i.e., $1.25B/yr).” Unlike federal money, that could continue indefinitely, unless shifted by the Legislature to other uses.

The funds could be used for other transportation projects in the state, Baruch Feigenbaum told me; he’s the senior Managing Director of Transportation Policy at Reason Foundation. “The state still has some funding they’ve set aside for that project,” he said. “And state officials have indicated that, if something would happen with the project, they would use those funds on other transportation improvements in the state.” Los Angeles and San Francisco would become the biggest beneficiaries of redirected funds, followed by Sacramento and San Diego.

He pointed out Newsom, while backing the Central Valley line, has been skeptical for six years about spending on the entire HSR project. In his first State of the State address on Feb. 12, 2019, the governor said, “But let’s be real. The project as planned would cost too much and take too long. There’s been too little oversight and not enough transparency. Right now there simply isn’t a path to get from Sacramento to San Diego.”

The Bay Area especially could use some help. The San Francisco Chronicle headlined March 31, “Rush hour is over in the Bay Area. Welcome to the era of permanent traffic.” Hybrid work schedules instituted since the post-COVID return to offices have replaced 9 a.m. to 5 p.m. work hours.

Then there’s the use, or abuse, of eminent domain by the High-Speed Rail Authority to grab many square miles of private property on which to build the train. In September 2022 the authority even distributed a pamphlet explaining the seizure process to affected property owners, “Your Property, Your High-Speed Rail Project.” For the Central Valley project, reported the Fresno Bee last September, “In 2013, the authority estimated it needed to buy all or parts of about 1,330 pieces of property for its three construction segments in the Valley. As of this summer, that had ballooned to 2,290 parcels, as well as 176 railroad-owned parcels.” Total cost so far: $1.5 billion.

Cities and property owners would be spared the disruption, even devastation, of rail lines left unbuilt. So everything depends on how much of the project actually ends up being built. Feigenbaum said unused parcels potentially could be sold back to the previous home or other property owners. “However, they might not want to come back,” he said. Using the properties for building roads, a logical choice, is doubtful because the state’s greenhouse gas mitigation efforts make it difficult to build new roads.

A good example is a Feb. 5, 2024 report in the Los Angeles Times on how Joseph Lyou, then a member of the California Transportation Commission, “raised concerns about providing it $202 million in state funds” to widen Interstate 15. He led a 3-3 Commission vote that “essentially stalled the plan.”

Another problem for how much more of the HSR will be built is state budget shortfalls. Newsom’s Jan. 10 budget proposal for fiscal year 2025-26, which begins on July 1, used “gimmicks,” in Sacramento parlance, to “balance” the budget by shifting funds to the future and making dubious cuts. But it did not factor the damage from the Pacific Palisades and Eaton fires occurring that very week. His May Revision to the proposal will have to take all that into account, as well as the hit to the budget from President Donald Trump’s tariffs, which will reduce both imports and exports at state ports.

A November study by the University of California warned, “As protectionist policies gain momentum in the United States, the future of California’s agricultural trade faces pessimism… . If a significant new trade war develops, California could see a quarter of its agricultural exports wiped out, costing the state’s economy $6 billion annually.”

On the positive side, the boom in artificial intelligence once again is pouring more Silicon Valley taxes into state coffers. The Legislative Analyst’s Office reported last November, “As the AI boom has supercharged California’s tech landscape, including sending asset prices for these companies much higher, the market value of equity pay options (and thus the state income tax that must be withheld on those options) has grown commensurately.”

Another budget complication is Los Angeles Mayor Karen Bass requesting $2 billion in state aid to make up for a $1 billion city budget deficit, plus rebuilding after the wildfires. Feigenbaum said that could impede city efforts to add more rail lines. But the city also is committed to making city transportation rides better before the 2028 Olympics.

With Newsom using his remaining months in office as a platform for his inevitable 2028 presidential bid, it will be up to the next governor to decide whether or not finally to kill the high-speed rail project, and on what to use the funds currently dedicated to its construction. Cities will have to adjust accordingly.