In 1999, just 703 people died from fentanyl overdoses. For the next ten years, those deaths remained relatively low. hitting 2,628 in 2012.

Yet from 2013 to 2023, fentanyl killed 376,197 Americans – a number roughly equivalent to the entire population of Cleveland Ohio. This doesn’t factor in the over 1.3 million overdose victims who received lifesaving doses of Narcan from EMS providers alone from January 2022 to September 2025.

Those are lives saved certainly but without treatment they are also deaths delayed. Add to this catastrophe the uncounted billions of dollars and lives lost in systemic and pharmacological violence, addiction driven economically compulsive crime, and the largely ineffective and expensive government response which has relied on the band-aid approach of administering Narcan to hide the problem under the guise of “harm reduction.”

The public’s frustration shows why President Trump’s decision to declare to Congress and the American people that we are in “armed conflict” with drug traffickers as well as the sinking of four “go-fast” boats by Navy destroyers has been politically popular.

500,000 dead Americans vs 16 alleged Venezuelan drug runners is an easy sell to Americans seeking the sugar high of an easy solution.

Whether the strategy offers sustainable long-term solution or is even legal is another story.

The purpose of the Armed Forces, in the words of Secretary of War Pete Hegseth, is to “kill people and break things.” They do this very effectively as the Houthis and the Iranian regime now know.

What they are not good at is law enforcement as that is not their purpose.

Four destroyed boats and 16 dead suspected drug smugglers certainly strikes fear in any would be smuggler about to embark on a northern voyage from South America. But whether that has a deterrent effect will be difficult to measure unless there is a corresponding drop in drug seizures, drug purity, and an increase in street prices.

It also creates an intelligence gap as dead drug runners tell no tales.

Beyond the constitutionality of fatal military action against drug criminals, there is a potential legal and moral issue as many cartel employees are dragooned into it through a coercive system that threatens retribution against families and loved ones for those who fail to live up to cartel demands. In short, failure can mean death and coercion is a legitimate defense to a criminal charge.

Interdiction is a necessary component of a drug control strategy. Properly resourced, the US Coast Guard, Drug Enforcement Administration, and Customs and Border Protection seize thousands of pounds of illicit drugs every year – 90 percent of which crosses the land border with Mexico.

Mexico is also where fentanyl is synthesized from precursor chemicals that are currently only made in one place in the world: the People’s Republic of China. Recently the PRC has called fentanyl a “US problem” and claims to have tightened controls on fentanyl.

At best, this is a polite fiction. At worst, fentanyl production is an active PRC destabilization strategy – described by one author as

Drug manufacturing and distribution networks are a many-headed-hydra and disarticulating those organizations in a succinct and lasting way requires intelligence gathering followed by action. Killing suspected drug runners and sinking their boats may make for good headlines, but they also bring a short-lived loss of inventory, and a difficult to measure deterrent effect.

In the end it will give them little more than a case of smugglers blues as expensive warships play a game of whack a mole searching for 60-foot boats in a big and empty ocean.

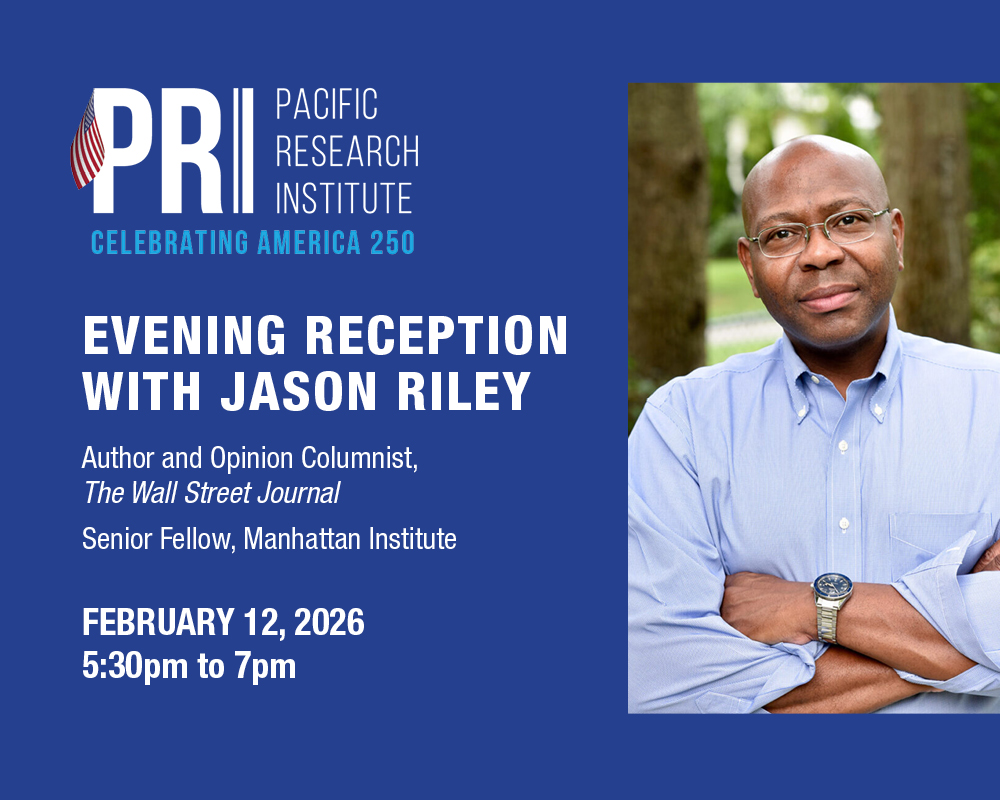

Steve Smith is a senior fellow in urban studies at the Pacific Research Institute, focusing on California’s ongoing crime challenges.