There’s an adage about crime statistics in progressive political and academic circles that can be summed up as the “perception exceeds reality school.” Put another way, Americans are simply wrong to be afraid of crime in the view of these so-called experts.

Recently, the New York Times criticized President Trump for calling crime statistics showing decreasing crime in Washington, DC “phony,” and opining later that his decision to deploy the National Guard in Washington, DC was wrong. The deployment may be wrong – but so are the declining crime statistics quoted by the president’s opponents.

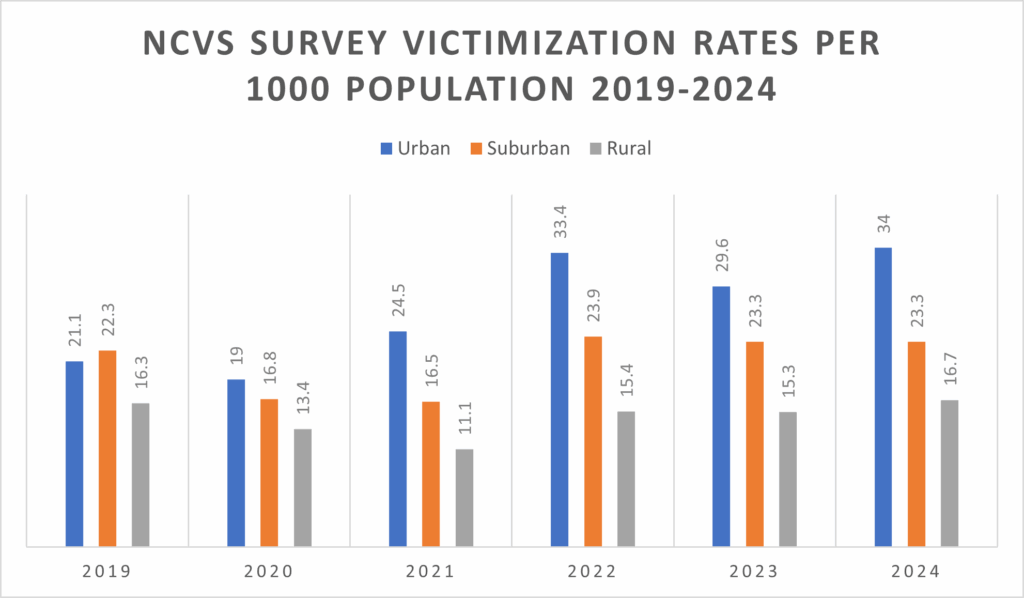

The September release of the National Crime Victimization Survey shows that from 2020 to 2024, urban violent crime increased 80 percent nationally.

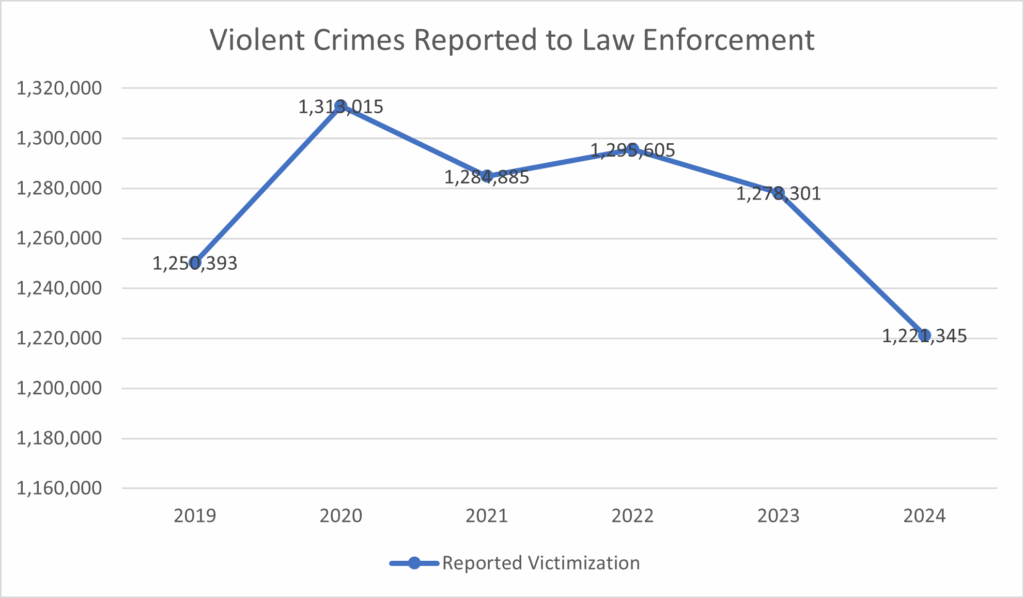

What the media and a lot of academics and statisticians are talking about is that reported crime is down.

A popular source for those statistics is Jeff Asher, who is known for his ability to compile homicide statistics by mining data from a number of cities who post frequently updated crime statistics on their websites and then compiling them in his Real Time Crime Index. Indeed, the index can be useful for year-to-date reported crime data and his choice of homicides and violent crime is intentional as reporting is higher for violent crime.

Asher is not alone.

Recently Ernesto Lopez from the Council on Criminal Justice issued a report entitled, “Crime Trends in US Cities: Mid-Year 2025 Update,” which uses a similar modality to Asher’s – large cities with public databases. This caught the eye of the Public Broadcasting Service, and Lopez was the featured guest on their program, Story in the Public Square.

The host, Jim Ludes, was encouraging when he began the broadcast, stating that “there is no acceptable level of violence or criminality in any community.”

Unfortunately, it went downhill from there when he argued, “the debate about urban crime and what to do about it is divorced from what the data actually says about crime in American cities.”

His meaning was clear: we are more afraid of crime than we need to be.

It’s not all bad, though, and Lopez’s report, which is far more informative than his interview, includes this in its conclusion:

Understanding recent crime trends is not a purely academic exercise. From 2020 to 2024, an estimated 13,500 more people were killed by homicide than in the previous five years (2015-2019). Beyond the legacy of trauma and other direct consequences for victims and survivors, murder and other crimes come with immense societal costs, reminding us that even during periods of declining violence, efforts to reduce victimization must remain a priority.

Unfortunately, reorganizing and reciting Uniform Crime Report statistics or even one’s own urban dataset of reported crime data is only half the story.

The NCVS gives us a hint of why:

- Urban violent crime victimization is at its highest level in 5 years

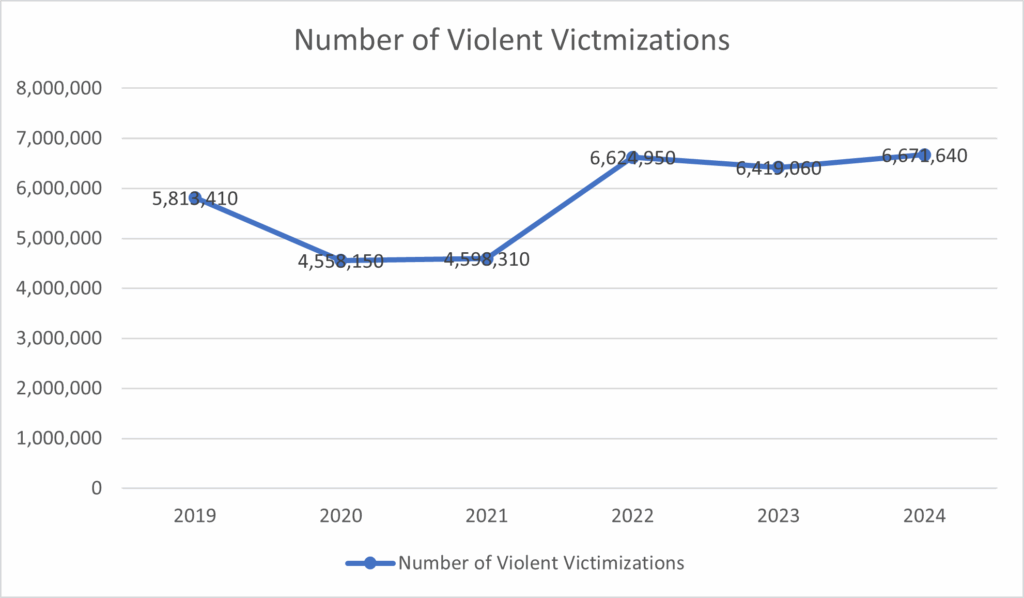

- The total number of violent crime victims is 6,671,640, its highest level in 5 years

- The number of victims reporting violent victimization is 1,221,345 – its lowest level in 5 years

A comparison of the NCVS with the Uniform Crime Reports (or Lopez and Asher’s datasets) yields what some criminologists call the “dark figure” of crime – the difference between victimization and reporting. It’s dark not in the sinister sense, but in the sense that unreported crime leaves policymakers and criminal justice agencies in the dark as to how to best prevent and respond to crime.

Only reported crimes are dropping, and this along with an increasing “dark figure,” which stands at 4.4 million, tells us most crime victims have opted out of reporting. This isn’t a new phenomenon as the two charts show. The increase in violent dark figure crime from 2020 to 2024 is 46.6 percent and represents a truly dire and troubling phenomena that exposes a concerning reality that people are losing faith in their country’s system of justice.

Increasing crime reporting (coupled with declining NCVS victimization statistics) should be the goal. Together, they indicate faith amongst the public that their institutions of justice are functioning and that crime is dropping.

So far, we are only halfway there.

Steve Smith is a senior fellow in urban studies at the Pacific Research Institute, writing about California’s ongoing crime challenges.