One somewhat overlooked but recent Supreme Court case contains potentially powerful implications for the private sector’s operational culture, especially in health care and education

West Virginia v. EPA centered around the question of whether the Environmental Protection Agency has the authority to regulate how electricity is generated. Motivated to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, under the Clean Air Act, the EPA attempted to wipe out the coal industry by requiring states to use only wind and solar sources of energy.

But should unelected administrative heads of agencies have such broad authority over the energy market? Comparing the EPA’s overreach to the unconstitutional eviction moratorium forwarded by the CDC and the FDA’s attempt to outlaw tobacco, the Supreme Court ruled that no, the EPA does not have that authority. Decisions of significant “economic and political magnitude” reside with Congress even if Congress delegates some powers to various administrative agencies

Those lines of authority between Congress and the administrative state are usually fuzzy, with Congress abdicating more authority than it should to unelected administrative officials. As this trend continues, the separation of powers (in this case separation between legislative and executive branches) as intended by the Founding Fathers is increasingly weakened.

As our practical government functioning has transformed from a strict democratic republic to a bureaucratic semi-oligarchical state, private institutions have shifted culturally as well.

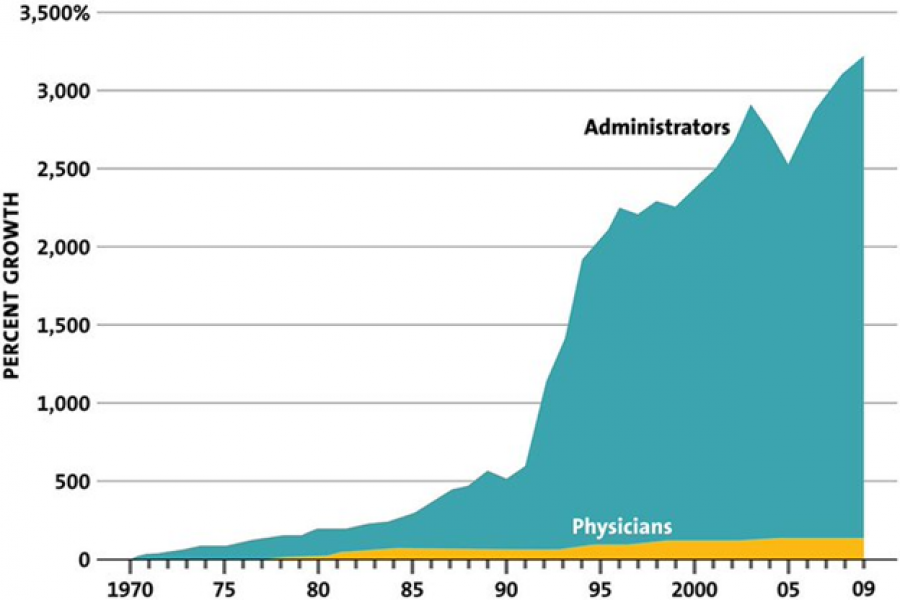

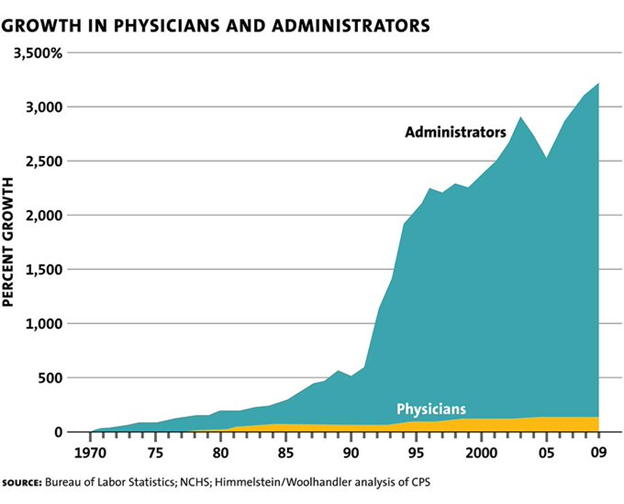

For example, the growth of health administrators relative to actual health practitioners has grown drastically since the 1970s.

Yet despite the excessive health administration staff, access to health care has decreased. Costs have ballooned to such an absurd degree that many forgo necessary care. And as I have written before, many physicians cannot afford to own private practices because of the costs associated with paying for administrative staff and insurance data specialists.

Yet despite the excessive health administration staff, access to health care has decreased. Costs have ballooned to such an absurd degree that many forgo necessary care. And as I have written before, many physicians cannot afford to own private practices because of the costs associated with paying for administrative staff and insurance data specialists.

In education, the cost of college tuition has outpaced inflation at a rate of 4.6 percent. But paychecks of professors have not inflated in kind. So where is the tuition money going? Over the last several decades, university administrative staff has grown tremendously.

Take for example, a telling study of the University of Minnesota’s payroll. From the years 2001-2012, the University’s management costs for administrative staff grew by 45.5 percent, while professor’s pay only grew by 15.6%.

Essentially, America’s youth are burdened with excessive school debt so that university can continue to hire unnecessary administrators – one for every 3 and a half students.

Philosophically and historically speaking, the connection between bureaucratic bloat in the public and private sector is demonstrated in the actions of President Woodrow Wilson and the thoughts of sociologist Max Weber.

In many respects, the concept of “separation of powers” died when President Woodrow Wilson took office. He argued that government agencies would act benevolently and must be freed from the constraints that limited the other branches of government. By creating independent administrative entities, the executive branch grew tremendously in scope and size.

Sociologist Max Weber, whose thought influenced Woodrow Wilson, forwarded a theory of bureaucracy. He thought that ideally, both the public and private sector should thrive on division of labor, specialized roles, principles of promotion, careerism, salary structure, with a particular emphasis on hierarchy and abstract rules. Clearly, these principles are easily recognizable: Weber’s thought has been hugely influential throughout the United States.

Ideally, Weber’s thought encourages public and private entities to function like a well-oiled machine. But as bureaucratic ideals have taken hold of the private sector, we see that it does not always pan out.

Because Weber’s theory of bureaucracy emphasizes specialization for career success, many individuals are motivated to create niche roles for themselves. Within these niche roles, it is then within the individual’s self-interest to expand their authority, even if it is technically outside expertise or legally vague. We see this trend in both the private and public sector.

While West Virginia v. EPA, does not formally affect how private entities function, the hope is that pushback on public entities’ constitutional overstep will lead to increased skepticism of bureaucratic culture in both public and private sectors.

McKenzie Richards is a Policy Associate at the Pacific Research Institute.